IN THE NEWS

North Atlantic Wild Salmon

Generally, one hears about exploitation of marine resources in the Southern Ocean, rather than in North Polar Waters. However, it would appear that Greenland is refusing to limit its wild salmon catch, and that this is threatening the survival of the North Atlantic Wild Salmon.

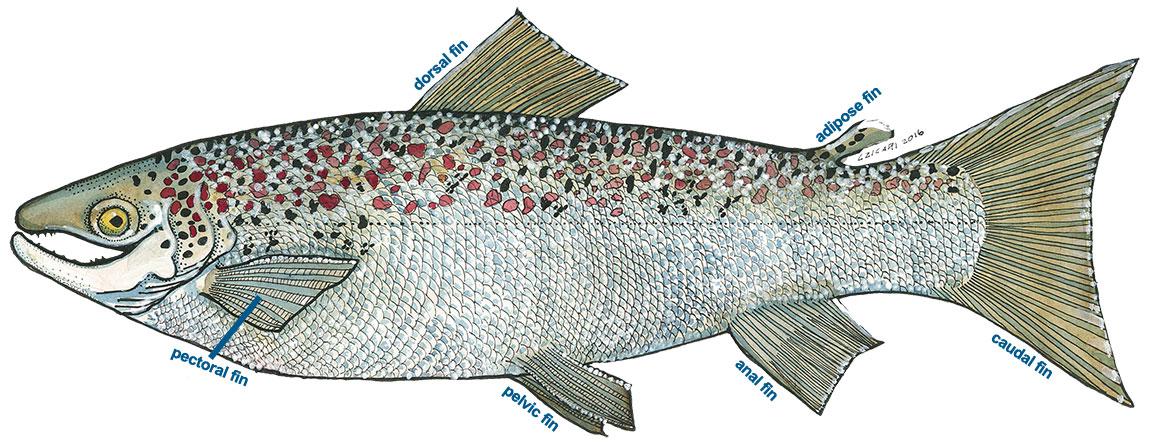

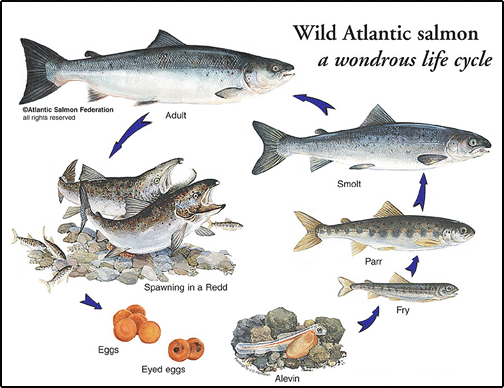

Salmon are a migratory species, and the North Atlantic Wild Salmon travels thousands of kilometers between some 2,000 European and North American rivers, where it breeds, and Greenland waters where it feeds.

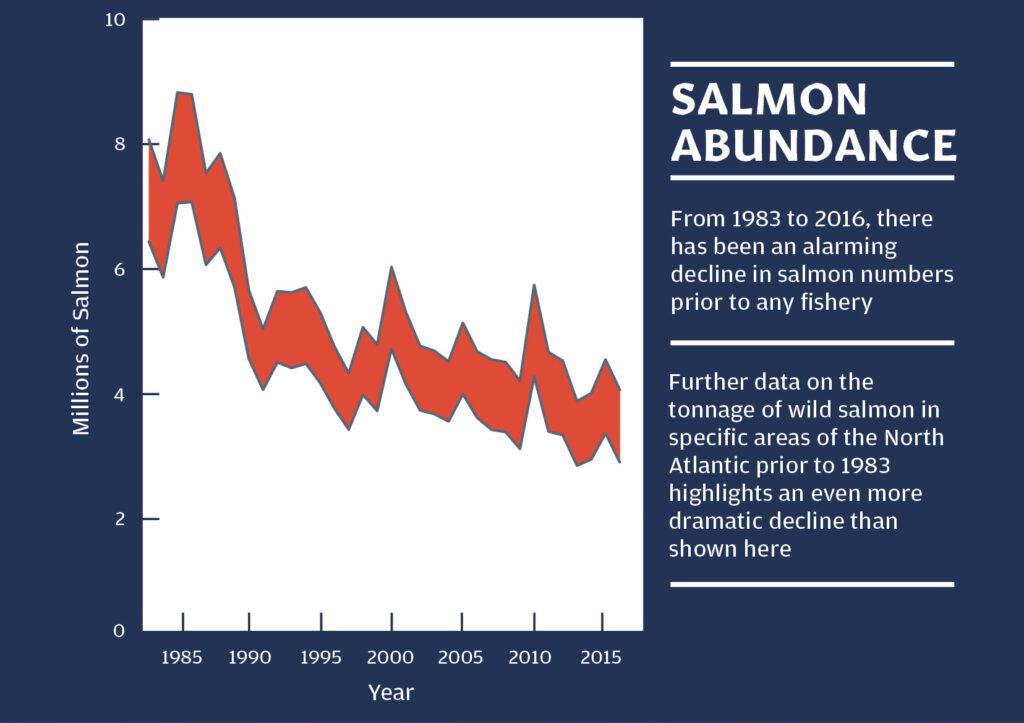

Salmon catches are governed by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation (NASC), which has been working since 1982 to manage sport and commercial fisheries. Canada stopped all commercial fishery for salmon on the East Coast in 2000, and almost all other regional fishery is on a catch and release basis. Greenland has had a commercial catch of 30tonnes, and due to ongoing concerns about salmon populations had been asked at the last NASC meeting to reduce its catch to 20tonnes. This request was based on advice from the International Council for Exploration of the Sea, which advised NASC that the current catch is unsustainable.

Greenland refused to accept a change in its catch limit, and will continue to take 30tonnes, although there is now no penalty for over fishing. The NASC will review matters in 2022 in the hope that Greenland will agree to a lower limit.

The fishery was reportedly healthy in the 1970’s, but has declined significantly since the 1980’s; see the chart below.

Information is mainly from a report in The Chronicle Herald (a Halifax NS newspaper) 15 June 2021 by Barb Dean-Simmons, Saltwire Network, supplemented by reference to the NASC web site and the US Fish and Wildlife Service website.

Sale of the mv Arctic

In this case it is something that should have been in the news, but wasn’t.

The April edition of the TMHS Scanner had a brief item regarding the sale of the mv Arctic for scrap to Turkey.

This legendary arctic vessel, built in 1978 at Port Weller ON, and was involved in most Canadian Arctic ventures that needed bulk shipments from then onwards. There are numerous references to her in Arctic Cargo, and she is covered in detail in Chapter 9.12.

The ship was working up to the end and carried her last load of concentrate from the Raglan mine in Deception Bay departing on 07 March. She arrived Quebec City to discharge 18 March; sailed for Aliaga on 26 March and was beached at 10:28UTC on 16 April. Her replacement1 Arvik1 is slow steaming towards Balboa and on 17 April was reported at 24.1929N 120.951W, with an ETA Balboa 26 April.

Glencore has an agreement with the local communities that there will be no shipping activity between 15 March and 15 June, so the new ship should be in good time for her first cargo of fuel and re-supply items inbound to the mine, and an initial load of concentrate outbound.

Banning Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) in the Arctic

Under pressure from an NGO – The Clean Arctic Alliance – The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has agreed to introduce an expansion to the MARPOL Convention that would ban the use and carriage of HFO in the Arctic. Canada has supported this move. A similar ban was introduced for the Antarctic on 11 August 2011. There, only cruise ships and vessels supporting research stations, had to comply. Most of the cruise ships operating in the Antarctic only use distillate fuels, but there was a noticeable dip in activity by large cruise ships that tend use heavy fuels between the 2011/12 and the 2017/18 season.

Not being able to either use, or carry HFO means ship operators must convert engines to burn only Marine Diesel Oil or Marine Gas Oil. These are distillate fuels, as compared with HFO and IFO, which are referred to as Residual Fuels, and marine engines work quite differently with them. Companies will have to spend money to change their bunkering and lubrication oil systems as well as making some technical changes to the engines. These changes may involve replacing components.

Thus the economic implications for the Arctic region, particularly the Canadian Arctic, are considerable. Baffinland Iron Ore employed 38 Panamax1 class ships on 82 voyages to move ore from its Mary River mine in 2019. Agnico Eagle Mines and TMAC Resources employ international flag tankers to bring fuel to their mines, there are two mines in Deception Bay in Northern Quebec, and the Port of Churchill MB needs international flag bulk carriers to move grains and pulses to market. Annual re-supply for communities employs Canadian ships, and the consequences of moving to distillate fuels can probably be managed through subsidies.

The problem facing companies that provide service to Churchill, Arctic communities and most mines is that this trade is only for about 150 days each year. For the other 200 days they have to operate in competition with ships that will not have had to invest in new fuel systems to meet an HFO ban. There may be a limited number of international flag vessels willing to make the changes necessary.

Time Line

The current information about an HFO ban indicates 2024 as the date for it to come into force. However, the HFO ban in the Antarctic started with a request to IMO in 2005, and it did not come into force until 11 August 2011, essentially six years later. A four- year time line for the Arctic is possible, but not probable, as IMO has distinct procedures to go through before MARPOL can be further amended.

When Transport Canada called for comments, I wrote the following submission, which challenged the rationale for the ban. Read Here

1 Ships designed to meet the dimensions of the old Panama Canal locks, and generally from 65-75,000dwt.

Harlequin Books Announces New Imprint

Recently Harlequin Books announced a new imprint called Dare, but few would be aware that the origins of Harlequin have a strong Arctic connection This is through Richard Bonnycastle, who joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1926, later becoming District Manager for the Western Arctic and Chief Fur Trader. He left the Company in 1945 to become Managing Director of the Advocate Press in Winnipeg.

There, he founded Harlequin Enterprises Ltd in 1949, as a paperback re-printing company. In 1953 they started publishing medical romances, and Richard’s wife, Mary, took over the editor’s role in 1954. She enjoyed romances published by Mills and Boon in Britain and persuaded Richard to acquire the North America rights. In 1957, Harlequin did, the romances were enormously popular, and the rest is history.

Photograph: Hudson's Bay Company motorship Banksland in the Western Arctic. Photo courtesy Earle Wagner

The Northwest Passage

In an article about the Arctic in the National Post on December 22 the usual media claim was made that large numbers of ships would traverse the Northwest Passage in the future. In supporting the claim the article stated that 33 ships made the trip in 2017. While the number is correct, it should perhaps have been qualified as to the make up of the transits:

- 23 pleasure craft, mainly under 15m length

- 4 cruise ships, one of which was the Canadian flag icebreaker "Polar Prince"

- 2 icebreakers

- 1 icebreaking offshore supply ship; the "Arcticaborg" on charter to Fathom Marine.

- 1 research ice breaker, the Chinese "Xue Long"

- 2 cargo ships, one of which was the Canadian flag tanker "Havelstern" in ballast

In fact, over the last decade 70% of all Northwest Passage transits have been by small pleasure craft; only 6% have been by ships that could be considered commercial, and only half of those have actually carried cargo.

Photograph: The Happy Rover in Bellot Strait, from BigLift web site

Yaks in Ungava Bay

An article by Richard Warnica in the National Post on December 30 recounted the efforts of the Canadian government to introduce Yaks to supplement Caribou in Arctic Quebec during the 1950’s.

This was not the only attempt to introduce alternative herd animals into the far north. Arctic Cargo notes the travails of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the 1920’s to introduce Finnish reindeer to Baffin Island in 1921. After delivering that year’s re-supply cargo, their ship, "Nascopie", sailed to Finland and loaded 627 reindeer and 161 tons of reindeer moss, which were delivered to Amadjuaq (a short-lived trading post between Lake Harbour and Cape Dorset) on Hudson Strait. Belatedly, it was discovered that Baffin Island lichen is not the same as Finnish reindeer moss, and the venture failed.

A more successful exercise was a joint venture between American and Canadian authorities to introduce reindeer to the Mackenzie Delta region of the Northwest Territories. In 1935, over 3,000 Russian reindeer were delivered to Canada via Alaska. The herd is still going strong, but is now privately owned by the Binder family. The herd winters at Jimmy Lake and crosses the Mackenzie River to their summer calving grounds at Richards Island, usually in March.

Photograph: from web sources www.spectacularnwt.com.

Le Wild West Show of Gabriel Dumont

This historical play opened recently in Ottawa and will then go on tour. A recent review in the Globe and Mail suggests a thought provoking spectacle relevant to the history of the Metis. However, as with much that is seen about the Metis (eg Louis Riel), the focus is on the end game, not on where the problems started.

Chapter 4 of Arctic Cargo explains the beginning of the conflict.

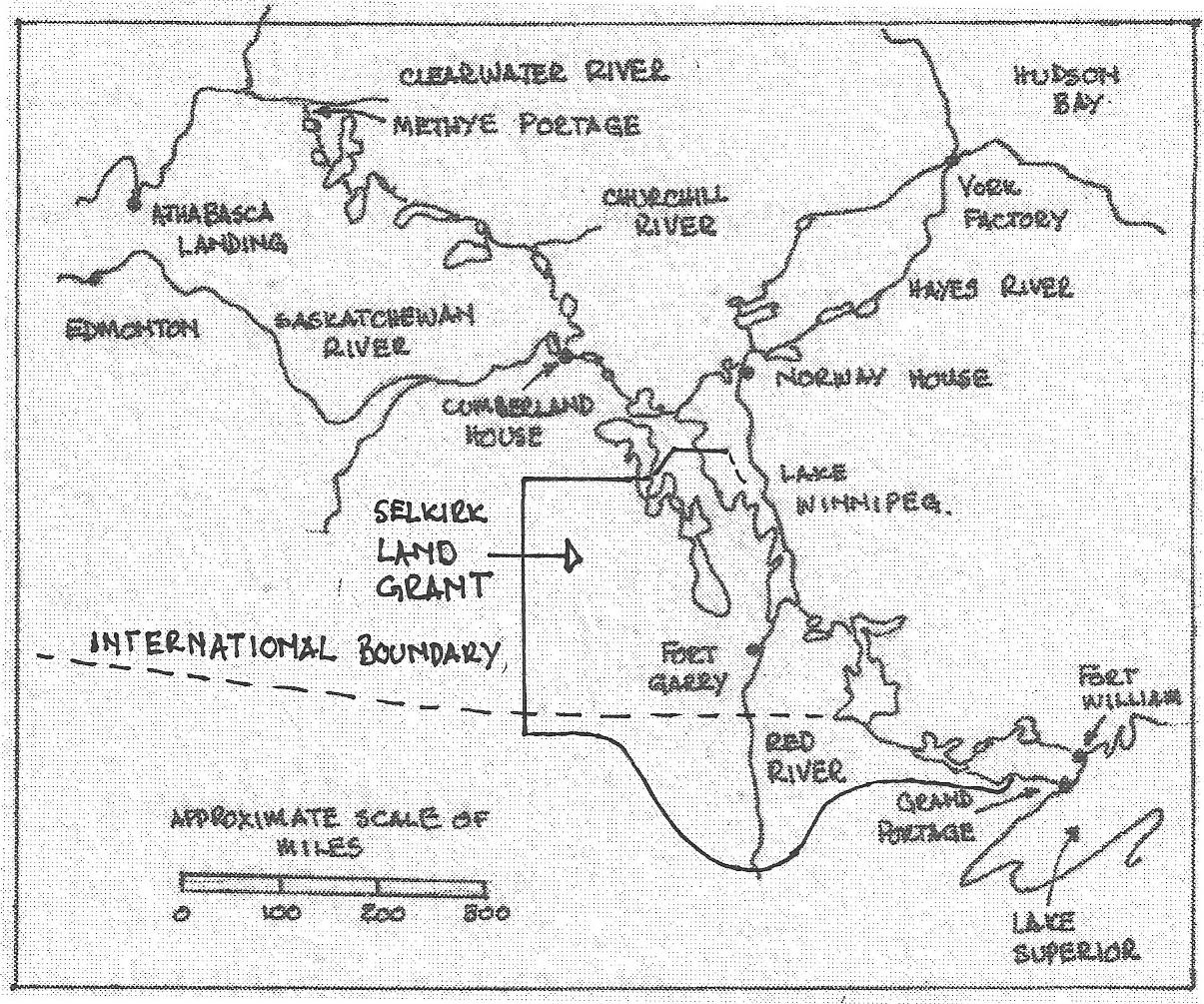

The Metis and the Northwest Company who were the “Canadian” fur company worked well together for many years until the misguided Earl of Selkirk took over the Hudson's Bay Company and used his share holding to "acquire" a land grant where he could settle displaced Scots (The Red River Colony). At this time (1811) the HBC had little interest in the far west of Canada, which was the NWCo’s domain. The colony, which was carved out of the HBC’s Rupertsland holdings cut across NWCo supply lines, and imperiled their critical pemmican trade with the Metis. The "grant" also covered much of the Metis homeland. Selkirk's agents commandeered NWCo and Metis winter food stocks for the Scots, banned the export of pemmican, and refused to recognise Indian and Metis rights. The situation deteriorated further, leading eventually to demands for a Metis homeland.

Sketch map showing the Selkirk Land Grant (click to enlarge)

The Film “Gold”

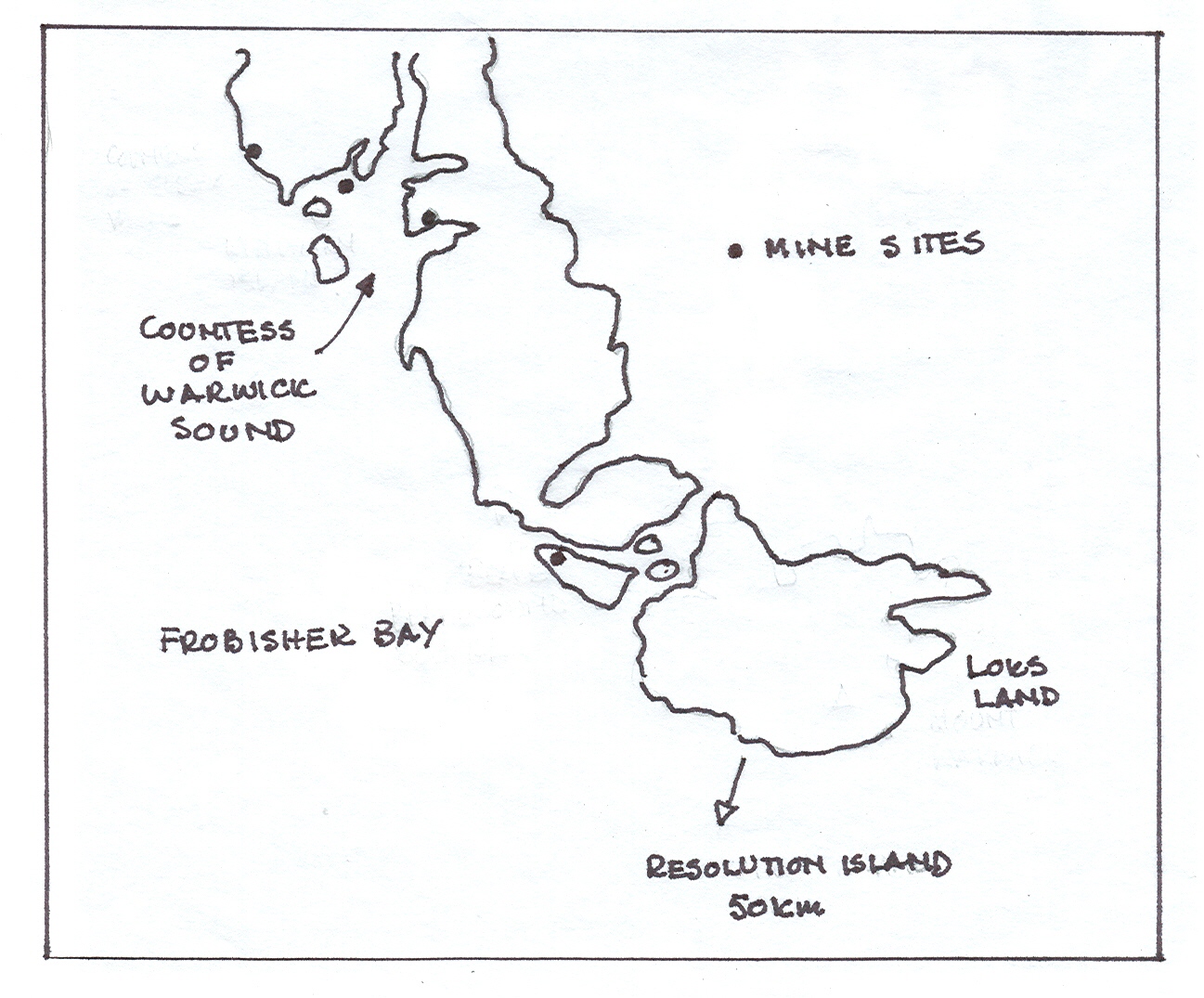

The plot of Gold bears some resemblance to the Bre-X gold fiasco of 1997. Although Gold’s fictional mine is in Busang, Indonesia, there was a similar event that took place off Baffin Island in the Elizabethan era. Arctic Cargo covers Martin Frobisher’s three voyages to Kodlunarn Island and other islands off the tip of Baffin Island, seeking gold from worthless rock. While shareholders in Bre-X reportedly lost $6bn, the investors in the Baffin Island scam, including Queen Elizabeth I, lost the equivalent of $18m in today’s money.

Location of Martin Frobisher's purported gold mine. (click to enlarge)

Asbestos

The Canadian federal government decision to ban the use of Asbestos from 2018 has been in the news recently, with comments about an identity crisis for the towns of Asbestos and Thetford Mines where the mineral was once mined. What has been forgotten is that forty years ago, Quebec had a major source of the mineral in Arctic Quebec near Deception Bay. Asbestos Corporation shipped about 2m tons of semi refined product to Nordenhamn in Germany for final processing and shipment to market. The mine operated from 1972 to 1983, and its assets were eventually re-used by Falconbridge for it's Raglan nickel mine. Chapter 9.5 contains a detailed discussion of finding Asbestos Hill, and the mine's development.

Asbestos Corporation dock with tanker alongside . Photograph courtesy of Harald Kullmann, WorleyParsons, mid 1970's

Northern Transportation Company Ltd is Declared Bankrupt

Since the 1930’s NTCL has provided transportation to remote communities on the Mackenzie River and the Western Arctic. In April 2016, the company was declared bankrupt, but under arrangements with the court provided re-supply services that season. The company also commenced disposal of assets. While these were initially characterised as "non-core", an application to the court in December to dispose of remaining assets to a numbered Alberta company understandably alarmed the Government of the Northwest Territories, who stepped in and bid $7.5m to ensure that equipment was available for the 2017 re-supply season and beyond. The GNWT, operating as Marine Transportation Services, ran a core fleet during 2017 ensuring communities received supplies. The book includes a Chapter about the company, its development in both the Western and Eastern Arctic and its role in community re-supply.

Photograph of NTCL tug and barge in Cambridge Bay mid 1980’s. Courtesy of Captain Todd Gilmore

Nanisivik Naval Facility

In August 2007, the Federal Government announced that the Nanisvik dock would be upgraded to serve as a northern base for the new Arctic Offshore Patrol naval vessels. Chapter 9.6 of the book digs into the history of Nanisivik as Canada’s first community mine, and the role of the Federal Government in helping finance it. The dock also had an important role in community re-supply and this is also covered.

Photograph of Ice breaker John A MacDonald at Nanisivik mid 1980’s. Courtesy of Captain Todd Gilmore

July 26th 2016 Omnitrax closes the port of Churchill

Chapter 8 of the book is profusely illustrated, and covers the history of the port from the late 1800’s to the present day. Included is a discussion of the political maneuvering behind the Hudson Bay Railway, and why the port was actually started at Port Nelson, 120km SW of Churchill.

The HBR has always been a problematic link, given that it is founded on permafrost. Climate change and torrential rains in May 2017 have caused major track bed problems as well as multiple washouts. The cost of repair has been estimated to be as much as $60m. As in its original construction, whether the HBR will be rebuilt comes down to politics. The port has never been economic, and the logistics problems that were supposed to be cured by construction of the port were essentially resolved in 1905 when the Dominion government completed updates to the St Lawrence canals and locks, enabling ships of 2,000dwt to sail from Lakehead to Montreal.

Photograph of SS Farnworth and SS Warkworth. 1931. First ships to load wheat at Churchill. Courtesy Library and Archives Canada C-022471…

Cost of Goods in the North

The cost of goods in the North has been in the news recently. Arctic Cargo contains extensive information about historic and recent costs of shipping. For example, in 1935 the Hudson’s Bay Company rate to Pond Inlet was $75/ton. The equivalent rate today would be $2,096.40, but the actual Government of Nunavut contract rate in 2012 was $362.83/tonne.

Photograph of goods coming ashore in Iqaluit in 2009. Courtesy of Luc Beland Canadian Coast Guard